Some of the earlier computers were rare ones. The Panasonic Sr. Partner is just such a computer. This was designed in Japan as a type of IBM clone back in 1983. It was one of the first clones to leave Japan for other shores. The computer was created to be portable, but not the way you would think of a laptop today. The “Sr.” stood for “Senior”, but just about the only “senior” aspect of this computer was its lofty price.

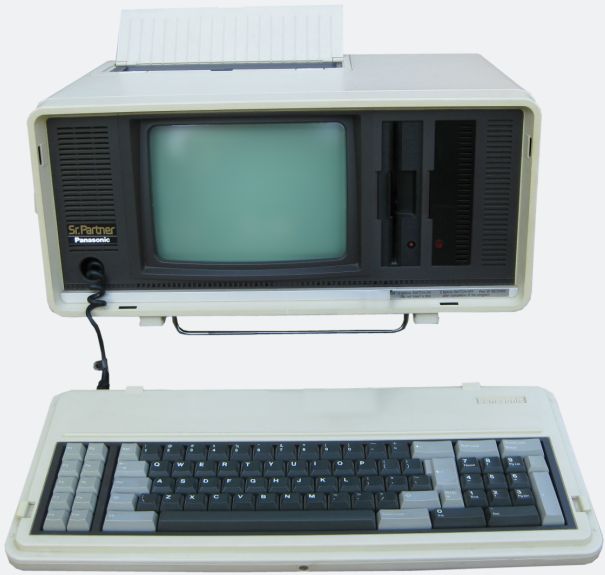

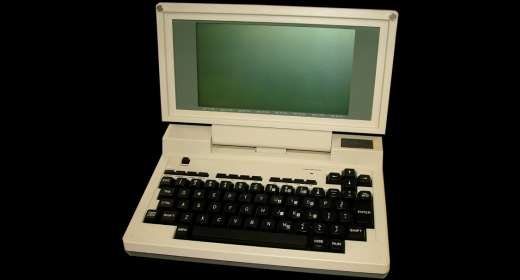

Japan, Korea and other countries were known in the past to make copies of much of the things manufactured in the United States. The Panasonic Sr. Partner is an example of this. This machine was designed to be an IBM clone. The monitor resembled an oscilloscope instead of what you might think of as a screen. It only supported text. It was the green centerpiece of the case after you removed the cover. It was flanked by two double density 5.25 inch floppy drives on the right. The other side sported a speaker and the wire connector for the removable keyboard. It was crafted with a plastic exterior with the same color, beige, that so many other personal computers had at the time. The Panasonic company was owned by the Matsushita company, but you would never find that name on the computer itself. Matsushita had been working in Japan for a long time and in the year they released the Panasonic Sr. Partner, they had just passed Hitachi as the largest maker of electronics in Japan.

Lurking on the inside of the Panasonic Sr. Partner was a 16 bit machine with a decent processor. It was a 8088, the same as the IBM models, that ran at 4.77 megahertz. The amount of random access memory ( RAM ) in the Partner was impressive. It had 128 kilobytes up to 512 kilobytes of RAM. Panasonic gave the Partner one slot for memory expansion. The video monitor was nine inches in diameter and rated as CGA ( Color Graphics Adapter ) which means it could handle color. It came in two resolutions. The first was 320 by 200 by 16. The second was 640 by 200 by 2. Panasonic put an input-output connector on the Partner that could handle parallel and serial connectors. One of the main differences in this luggable computer was that a printer was integrated into the machine. Like a regular printer, a user could insert paper into the top of the case of the Panasonic Sr. Partner and have a printout. There was a port for a RGB monitor and Panasonic included $1500 worth of software with the deal.

The operating system for the Panasonic Sr. Partner was MS DOS, since this was a clone of IBM computers. The version could not have been higher than 2.0 since that was the highest available at that year. As mentioned earlier, this computer was going to be expensive. It was priced at $3,500 dollars. Sales of the machine were not all that brisk and there were no later versions.

Like many of the other portable computers of this era, the Sr. Partner is collectible but not all that rare. A working Sr. Partner can sell for under $100.00. But, if you find one in excellent working condition with software and perhaps a carrying case then the price can reach $200.00.

My dad had a Nixdorf rebadged version of this, called the Nixdorf PC-01. When he was done with it he let me have it, as a six or seven year old kid, so technically this was my first ever computer I suppose!

It was a solid machine in its day, in every sense of the word. Don’t be fooled by that ‘portable’ tag – the thing weighs a good 20kg or so!

I’ve still got it up in the loft. I’d imagine it still works. Might have to dig it out and have a play for old time’s sake…

I had one of these! The article says, “Like a regular printer, a user could insert paper into the top of the case of the Panasonic Sr. Partner and have a printout.” That’s somewhat misleading. It did not work like any “regular printers” of the time in that it had a thermal print head, and it took a roll of standard thermal FAX paper, which was popular in FAX machines of the era, not computer printers that used ink ribbons and regular copy paper. In Japan, FAX machines were everywhere. They weren’t as popular in America at the time yet. But this printer produced printouts that were much more clear than those made by dot-matrix printers, probably because they had higher-density print heads that simulated dot-matrix print heads. You couldn’t print Japanese characters on a dot-matrix printer that was readable, so they used thermal print technology. The nice part about that was you didn’t need any ink or ribbons, which is how they were able to squeeze a printer into these boxes — it was basically a FAX machine adapted to run from a PC’s parallel port.